Looted artifacts from the Asante kingdom have been unveiled in Ghana after 150 years, following their confiscation by British colonizers.

The Manhyia Palace Museum in Kumasi, the heart of the Asante region, witnessed an enthusiastic reception as Ghanaians welcomed the return of 32 cherished items. “This marks a significant day for Asante and the entire African continent.

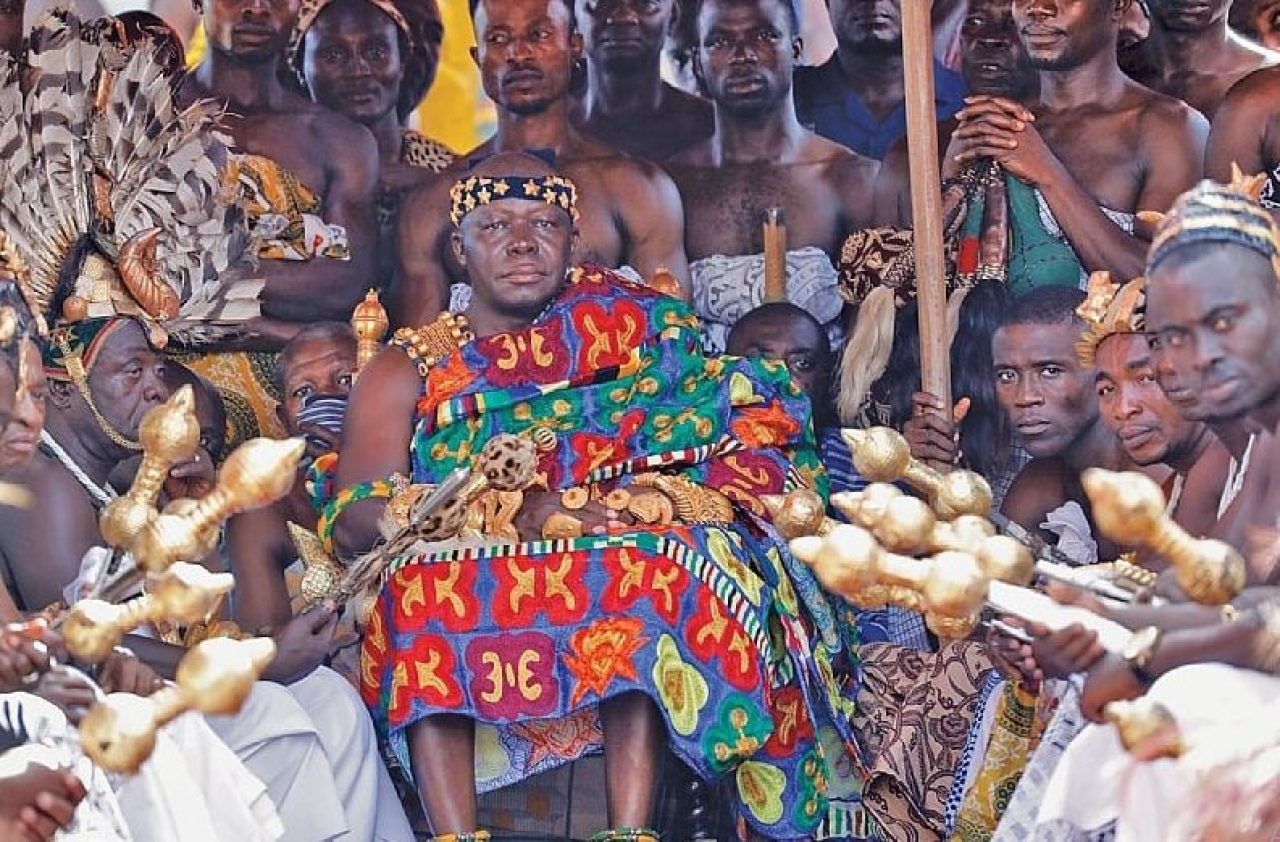

The essence we hold dear has been restored,” declared Asante King Otumfuo Osei Tutu II. The artifacts are currently on loan to Ghana for three years, with the possibility of extension.

The agreement involves the Asante king and two British museums, not the Ghanaian government, underscoring the symbolic significance of traditional leadership in the modern democratic framework of Ghana.

“Our dignity is restored,” Henry Amankwaatia, a retired police commissioner and proud Asante, told the BBC, over the hum of jubilant drumming.

Certain artifacts, often referred to as “Ghana’s crown jewels,” were taken during the Anglo-Ashanti wars of the 19th Century, notably the renowned Sargrenti War of 1874. Additionally, items such as the gold harp (Sankuo) were presented to a British diplomat in 1817.

“We acknowledge the very painful history surrounding the acquisition of these objects. A history tainted by the scars of imperial conflict and colonialism,” said Dr Tristam Hunt, director of the Victoria and Albert Museum, who has travelled to Kumasi for the ceremony.

Among the returned artefacts are the sword of state, gold peace pipe and gold badges worn by officials charged with cleansing the soul of the king.

“These treasures have borne witness to triumph and trials of the great kingdom and their return to Kumasi is testament to the power of cultural exchange and reconciliation” said Dr Hunt.

One of the returned items, the sword of state, also called the “mpompomsuo sword” holds great significance for the Asante people.

It functions as a symbol of authority, employed during the swearing-in ceremony for paramount chiefs and the king himself within the kingdom.

According to royal historian Osei-Bonsu Safo-Kantanka, the removal of these items from the Asante people represented the loss of “a portion of our heart, our essence, our entire existence.”

The return of these artifacts is both significant and contentious. British law prohibits national museums like the V&A and British Museum from permanently repatriating contested items in their collections, leading to loan agreements like this one as a means of facilitating the return of objects to their countries of origin.

While many Ghanaians advocate for the permanent retention of these ornaments, this new arrangement serves as a workaround for British legal constraints.

African nations have consistently demanded the return of looted artifacts, with some successfully regaining ownership of valuable historical pieces in recent times. For example, in 2022, Germany returned over 1,000 Benin Bronzes to Nigeria, acknowledging it as a step toward addressing a “dark colonial history.”